The Voice of Flowers

Instead of scorning the woman that stole my vision, I found beauty and wisdom in music. Now, I’m helping other visually impaired musicians do the same…

EXCLUSIVE | 4 min read | As told to Helen Croydon

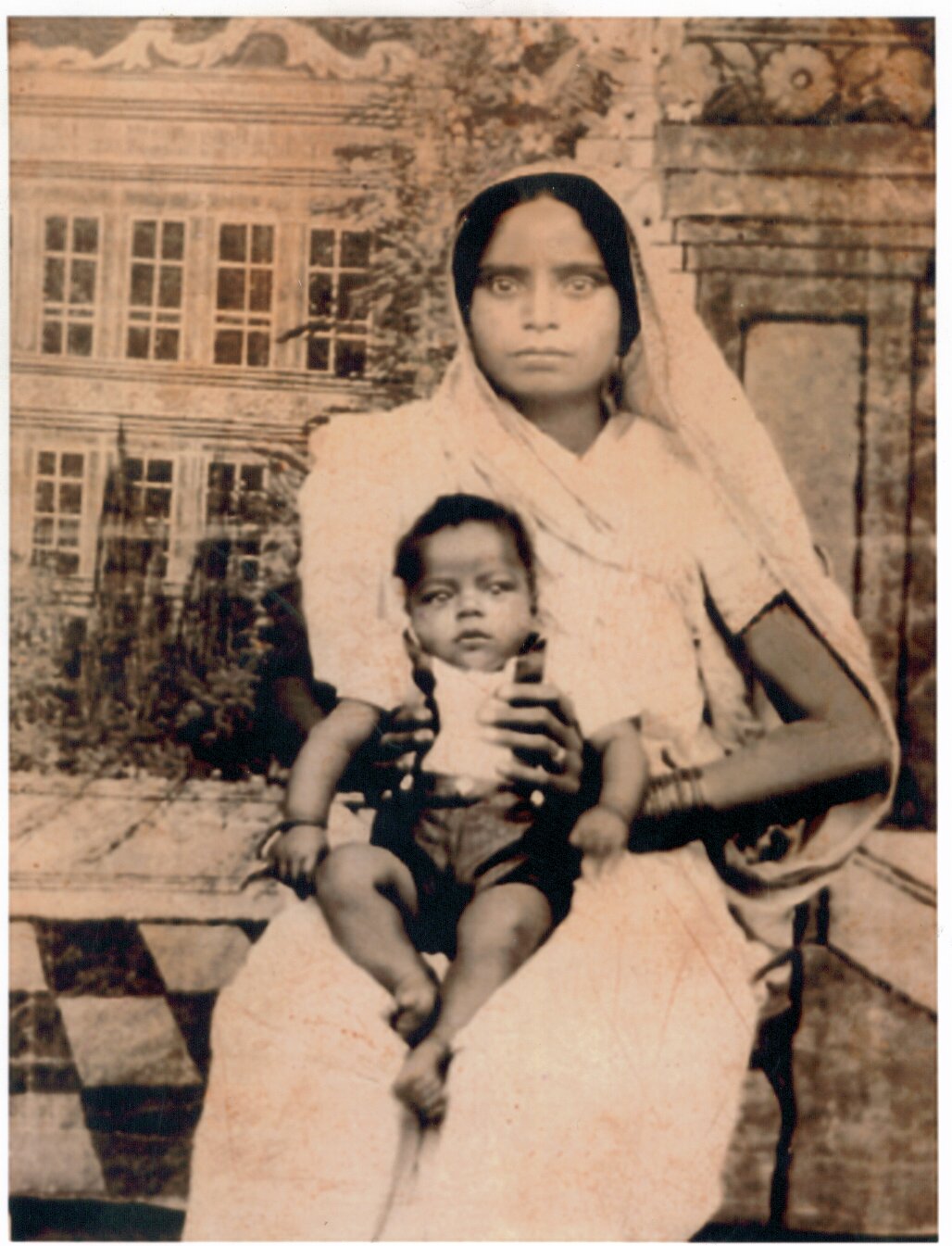

My mother was just 15 when I was born in a village in Uttar Pradesh, North India. Six days later, the day of Bhay Mata, my mother, Shakuntala, had a prophetic dream. She saw us floating in space surrounded by people dancing and singing. My parents concluded that one day, I would be a great musician.

When I was eight months old, during the Indian monsoon season, the village roads turned into muddy tracks and flies swarmed around cattle and swampy pools spreading dirt and disease. I caught an eye infection.

My parents loaded up the bullock cart to take me to the doctor but on the way, it got stuck in the mud. My mother was distraught until one of the neighbours offered to help treat my eyes, explaining she had cured her own children of the same problem.

The friendly villager prepared a potion, grinding up alum (potassium), naphthalene (from coal or petrol) and opium into a paste, before placing it inside my eyelids and bandaging my eyes. She instructed my mother to leave it on for three days and nights. I screamed the whole time as the toxic potion, unbeknown to my parents, burnt through my eyes and destroyed my optic nerves.

When my mother removed the bandages, there was a gory mess where my eyes had once been. She hoped that I would heal but it quickly became clear I had lost my sight completely. My parents believed what had happened to me, although tragic, was my destiny.

And there began my journey into the rich and wonderful world of sound. By my first birthday I happily imitated the loud street hawkers selling fruits and vegetables around the village. I sang along to gramophone records, which the neighbours played, copying lyrics and using my mouth and hands to imitate the drums and instruments – even the scratching sounds of the vinyl.

When I began crawling, my mother placed bands of tiny bells around my ankles so they could hear me if I wondered out of sight. Good job too, as once, when the neighbourhood was preparing a wedding feast, I crawled up the stairs to the flat roof searching for the source of the music that was being played, oblivious of the huge cooking pot beneath me in the yard. Someone noticed the tinkling of my anklets above them as I was dangling over the edge of the roof and rushed up to whisk me to safety.

I soon discovered all the noises I could make around the house, banging and tapping the plates and the pots. My mother sang to me and played harmonium – a keyboard with bellows operated by foot – and folk drums like most of the women in the village during holy days and village ceremonies.

We were once travelling on the train and I began singing a song I’d heard on the radio. Oh God if only I knew your address, I would write you a letter. The carriage burst into applause and I was carried through the length of the carriage on people’s shoulders so everyone could hear. It was in that noisy, excited carriage that my parents realised that music would carry me through this life.

Music was second nature to my father, and helped him to express his joy and his sorrow. He taught me the Hindu sacred verses of the epic Bhagavad Gita in Sanskrit, which I was soon able to recite by heart. Every morning, I strolled back and forth on the balcony, chanting the beautiful verses. He also taught me to meditate sitting cross legged on the flat roof for many hours. ‘If you meditate,’ he told me, ‘you can see without your eyes.’

My parents had no idea how I could be educated, but when I was six, my father heard about a blind school in Gwalior. We travelled 300 miles by train to visit the boarding school.

I sang and played the harmonium for the headmaster and he became very excited, insisting that I stay and perform to raise money for the school. My parents left me at the school - and to my fate - believing it would be easier for me. I spent a long time searching for a reason why, but in those days, nobody bothered to explain anything to children. We had to just cope. But it made me resilient and tough.

The children and teachers there were also blind. Until then, I hadn’t understood that I was too. I learnt to read Braille, and was introduced to many musical instruments. I was soon put in charge of the school orchestra even though I was the youngest.

One day, I touched a beautifully shaped instrument and wanted to pick it up. I was told I was too little but I cried and cried till they gave it to me. That was the sitar. As soon as I held it I started to play a tune. Since then, I have been with sitar, and it has been with me.

After I left school, I taught my family to weave chairs to sell, but soon, I realised it was more lucrative to perform music. I discovered that I could help my family out of poverty with my music. It was my ticket to freedom.

I grew into a man determined to be independent. I did not want to be pitied, but respected. I found work in music shops in Agra, where tourists visited the Taj Mahal and tried out Indian music, popularised by songs like Within You Without You, by the Beatles.

I took a job as a music professor at a local college and often taught foreign visitors. One student, Vincent, later sent me a ticket join him in France and become his tutor. I arrived alone there aged 28, with $22 in my pocket and a sitar in my hand.

The culture shock was intense. I had to start from scratch; learning French; finding vegetarian food with some flavour; accepting the different attitudes to religion, relationships, and money. Soon after arriving, I was robbed, but I had good fortune too. I met my future wife Linda in Paris. She brought me to London, much to the initial shock of her family.

I’d always been told I was ugly and skinny, so it surprised me as much as them that anyone would fall in love with me. We married and had two children, Benjamin and Leela. London became my permanent home.

Gradually, I built up my music career, with Linda helping me set up gigs, go to auditions, and record albums. It was a slow process. I wasn’t able to get a manager or agent, something I perceived as a prejudice against blind musicians.

I got by on word of mouth alone and was hired to play the sitar and other instruments on tracks with mainstream music stars, including Massive Attack, Annie Lennox, Oasis, Boy George, Sheila Chandra, Future Sound of London, Soul II Soul, Shakira, Kaiser Chiefs, Doves, Madness, Pepe Habichuela and Manitas de Plata.

It was wonderful playing with these artists but it hadn’t happened with any level of ease. I had grafted for years to bring my music into the mainstream. That struggle set me thinking and in 2012, Linda and I set up the Baluji Music Foundation, to help other visionally impaired people get into music. My efforts were honoured in the most spectacular way, when in 2017, I received an OBE from the Queen for services to music.

Linda and I went to Buckingham palace where Prince Charles awarded me my medal. He said my life ‘was a journey from village to privilege’. I was very proud and grateful that my adopted country had embraced and recognised my work.

A year later I set up The Inner Vision Orchestra, a professional orchestra made up of blind or visually impaired musicians – and the only one if its kind in the UK – to promote other talented, blind musicians because nobody else was giving them any exposure and they thoroughly deserved it. Our work is deeply gratifying.

Some years ago on one of my many trips to India, I visited the village I was born in and met the woman who had blinded me with her herbal medicine. I touched her feet out of respect and thanked her. Blindness has been her gift to me and opened up a whole new world.

Baluji Shrivastav’s latest album, Voice of Flowers, is available on Apple, Spotify and Arc Music. The Inner Vision Orchestra host music workshops for anyone who is visually impaired, with all musical abilities welcome. Visit Baluji’s website for more information.

Like this article? Help us commission more like it by donating the cost of a cuppa on Ko-fi.

Sharing this article on your social media, and following us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter are also a great way to support our independent, self-funded platform.

We encourage debate, but trolls are not welcome. Please read our comments policy before contributing.